Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker were two young lovers who went on a violent crime spree during the, “Great Depression”, in the American Mid-West. Between 1932 – 1934 they robbed countless stores, a few banks and murdered at least nine police officers and four civilians. The press at the time glorified their exploits as something akin to Robin Hood’s stealing from the rich to give to the poor. In 1967, Arthur Penn made use of his love of the European new wave cinema to create a fresh new crime film through the terrible exploits of Bonnie and Clyde.

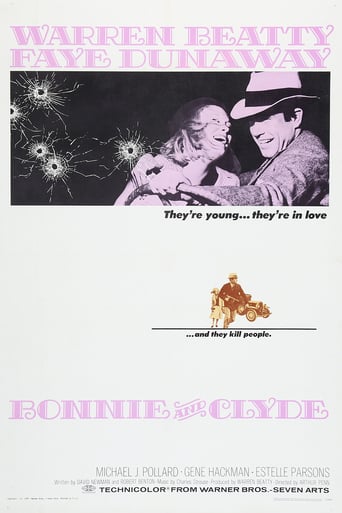

Right at the beginning of the movie, I knew that this was something different, as a completely naked Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway in a star making performance), watches as some punk named Clyde Borrow (Warren Beatty playing against type), tries to steal her mother’s car. Instead of making him stop, she encourages him to take her along for the ride. Clyde just got out of prison and he likes to steal. His outlaw persona is a big turn on for Bonnie, who encourages him to graduate from stealing small stores to robbing banks. They convince a dim-witted gas station attendant named C.W. Moss (Michael J Pollard) to become their getaway driver and are eventually joined by Clyde’s older brother Buck (Gene Hackman) and his hysterical wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons). The movie follows them through a few of their crimes and some of their edgy escapes from the police. They enjoy reading their own press about their escapades and begin to feel as if they are invincible.

What I found so fresh and revealing about the movie was its portrayal of the gangsters as nothing more than stupid poverty-stricken lowlifes, which is probably what they were. There is no depth of meaning or feeling in any of their conversations with each other, they seem to get off living in a constant state of fantasy, and the fact that it took two years for the authorities to stop their crime spree tells me more about the competence of the police then anything about their ability to be cunning. Penn and his scriptwriters understand this, and the Bonnie and Clyde shown here are not very glamourous. They may be attractive in a physical sort of way but are shown to be empty and rotten inside. Yet they are the heroes of the movie, which is one of the main reasons Penn’s film has become so influential.

Penn made use of a new theatrical device call squibs, which is an explosive charge filled with fake blood that gets detonated in the actor’s cloths when they are filmed being shot, adding realism to the violence. The ramifications of seeing skin being torn by bullets was a new thrill at that time, and Penn’s artistically aesthetic use of the painful effects of violence was a big turn-on for audiences of 1967, which continues to be true today. Coppola, Scorsese, Peckinpah & Tarantino, among others, with their spectacular violent set-pieces, owe a lot to, “Bonnie and Clyde”.

The movie is also much more then a depiction of colorful violence. There contains within its simple story many brilliantly conceived shots that constantly veer between slapstick and horror. The desperado couple are shown introducing themselves at the beginning of each robbery, taking pride and pleasure in their notoriety. These introductions are almost comedic with their clean cut, almost slapstick tone. When the same robberies revert to terrible violence without warning, the result is in many cases heart stopping, as these gritty spurts of realisms would immediately make me aware that I was viewing the acts of cold-blooded criminals.

These criminals are not depicted as cardboard psychopaths like the gangsters of Hollywood’s golden age, and Penn uses the French New Wave style in his depiction of these young, wayward, and basically stupid hoodlums. Their planning is non-existent and their survival, while it lasts, is based on luck. In one scene, the gang kidnap an innocent civilian couple, take them for a ride, while treating them as friends, laughing and joking together, until one wrong word causes them to be abruptly dropped out of the car. While nobody really gets hurt in this scene, it gives an insight into the mind frame of Bonnie. The movie however is not all free and loose like the European movies of the time. Penn uses a lot of first-person perspective on how he films some of the action. For example, after one robbery, the bank manager chases the gang’s car while they attempt to drive away and we see the manager get shot in the face from the perspective of Clyde, who did the shooting, which serves to personalize the deadly violence of the shooting.

“Bonnie and Clyde” is one of those rare movies that signifies a turning point in cinema history. The movie paved the way to not only more realistic crime drama, but to a more open and mature interpretation to life and crime. It is a movie containing dynamic power that stays fresh with each viewing. It is cinema at its best.